Growing up just outside of Washington, D.C., many of my childhood memories are intimately entwined with U.S. history. My mother, an elementary school teacher, wanted us to see all the historic sights on the east coast and so we travelled every summer – to Williamsburg, to Plymouth Rock, to Kitty Hawk. But we also went to downtown D.C.: the hallowed halls of the Smithsonian where I saw dinosaur exhibits, the Star Spangled Banner, and the Spirit of St. Louis; the National Gallery of Art where I was mesmerized by the history of the world displayed through portraits and landscapes and sculptures; the National Zoo and the first sights of giant pandas on loan from China.

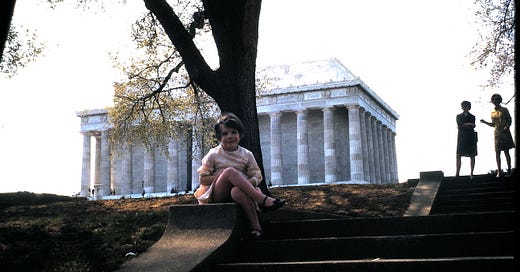

Every 4th of July we watched fireworks sitting by the reflecting pool near the Lincoln Memorial, listening to marches by John Phillip Sousa. The memorials were my favorite. Lincoln with its seemingly endless steps, Jefferson by the tidal basin surrounded by flowering cherry trees, and then later, the Vietnam Veterans memorial with its black granite etched with names. Every time I went by “the wall” as it’s known, there was at least one veteran scanning for names of fallen comrades with tears and grief.

As a child with a big imagination and a love for stories, this felt like being raised in the heart of a living myth.

America. In glass display cases and marble.

I loved her.

Then I got older.

Watergate hit when I was 12, and then stagflation of the 1970s with cars lined up to get gas on odd or even days. I tried to find the America I loved through reading historical fiction - the Kent family chronicles by John Jakes – but I saw even more complexity in our history. Something was shifting in me. I remember watching Roots in 10th grade and feeling, maybe for the first time, the full weight of our contradictions - the brilliance of our founding ideals, which I loved, and the deep, painful distance we’ve yet to cross. I realized history wasn’t just what happened out there but was something alive and unfinished.

This changed my love for this country from an immature love that required perfection - that only saw the polished and powerful - to a mature and more durable love. A kind of love that doesn’t flinch at flaws. A love that acknowledges harm yet yearns for healing.

A love that believes we are still becoming.

Superficial love often requires perfection. It’s fragile, because it depends on a kind of performance: "I love you if you meet my expectations." In the context of a country, this might look like only embracing the parts that are shiny, strong, and successful. It’s the waving of the flag without asking who got left behind in the wind. Love that demands perfection is brittle. It shatters under pressure. But love that sees clearly - that stays in the room even when things are messy - is the kind that transforms.

Deep love can hold contradiction. It says, “I see you. I know your history. I know the harm and the healing, and I still choose to stay.” That kind of love has memory. It has humility. It doesn’t confuse critique with betrayal. In fact, it understands that calling something to grow is an act of greater love, not less.

In exploring our history, this kind of love shows up in stories of those who had been deeply marginalized or wronged by U.S. society yet still chose to work for a brighter tomorrow. I think of the Navajo Code Talkers who used their language to create an unbreakable code during WWII, serving a nation that had spent generations trying to erase their culture.

And the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, which was a WWII unit composed almost entirely of second-generation Japanese Americans (many with families in internment camps), who became the most decorated unit in U.S. military history.

Or how about Fannie Lou Hamer, who was born the youngest of 20 children to Mississippi sharecroppers. She endured poverty and brutality yet rose to become a powerful voice for Black voting rights in the mid-20th century.

These examples – and I could go on – highlight people who loved this country enough to want to make it better. To live up to the initial promise that all of us are entitled to the same rights.

In spiritual terms, we often speak of grace — the idea that we can be fully seen and still fully loved. Maybe it’s grace we should show our country. Not as an excuse for inaction, but as the soil where transformation takes root. Abiding love doesn’t mean we stop telling the truth. It means we love through the truth. Becoming better, stronger, more fully alive by acknowledging our collective growing edges.

Think about the love you’ve had in your life. When have you felt most loved? Was it when someone said, “you’d be so pretty if you’d just lose weight”? Probably not. That kind of “love” implies, “thou shalt change or I will not love you” rather than “I see you – all of you – strengths and growing edges – and I love you.” Hiding your true self in order to be loved is painful. And loving someone – or something – only when it or they meet your ideals is not real love. That’s infatuation. And infatuation burns out when the shiny veneer wears off as it always eventually does.

We don’t love our children, friends, or partners only when they’re perfect. We love them through their growing edges. Why should it be different with the country that shaped us?

To love this country is to name its wounds and commit to healing them, not blind allegiance, but deep engagement. Maybe true patriotism isn’t about declaring our nation flawless, but helping it grow into the vision it has yet to fully embody. Loving this country doesn’t mean denying its failures — it means facing them so we can write a better story together.

As an aging adult, I still love the museums, the monuments, and the memorials of D.C. But now I see them clear-eyed — through my grief, through my fear, and through the lens of a country still unfinished. I grieve the hatred, the distortion of history, the retreat from compassion.

And I fear what we might become if only some are allowed to be included in ‘We the People.’

For me, ‘We the People’ means everyone. No exceptions. It means honoring the dignity of all — across race, faith, gender, and origin — and living into the truth that our democracy has consistently expanded, not contracted.

My love doesn’t whitewash the past. It honors it by telling the truth — even when the truth breaks your heart. And still, I reach for the promise — the one I first glimpsed sitting by the Lincoln Memorial as a child, and the one I now fight for with my whole, imperfect heart.

The promise of a more perfect union. The promise of dignity and equality for all. The promise that love — honest, unflinching, inclusive love — can still be the force that brings out the best in us, and maybe even helps us become the nation we were meant to be.

Joni Miller, Ph.D. is a writer, researcher, spiritual coach, and speaker who uses her knowledge, education, and love of all things spiritual to help others find their unique spiritual path. www.SpiritualGeography.net

Share this post